implementation-methodology---version-2-audit-and-mitigation

6.1. Architectural approach

The transition from Version 1 (Reactive) to Version 2 represents a fundamental paradigm shift from a simple “If-Then” script to a state-of-the-art, autonomous Multi-Agent System (MAS). While Version 1 demonstrated the viability of the JADE framework, it suffered from the “Blind Execution” problem—killing any process that exceeded a threshold is a strategy too reckless for production environments.

In Version 2, we architected a system based on the “Zero-Trust” security model. In this model, high resource consumption is not automatically classified as malicious; instead, it is treated as an anomaly requiring investigation. This necessitates a decoupling of monitoring (sensing) from diagnosis (thinking) and remediation (acting).

This approach is considered one of the most robust and scalable architectures in distributed systems engineering for three key reasons:

- Resource Preservation: The persistent agents (LocalAgent) remain extremely lightweight dumb sensors. We do not burn CPU cycles on client nodes performing complex analysis unless absolutely necessary.

- Contextual Awareness: By physically migrating a ScoutAgent to the node, we gain “local context”—access to kernel-level structures (/proc) and file systems that are often inaccessible to remote RPC calls.

- Surgical Precision: Remediation is no longer a system-wide reboot or a blind kill; it is a targeted extraction of specific malicious threads, ensuring business continuity for legitimate services.

6.2. Technical workflow

Phase 1: anomaly triggering

The cycle initiates at the CentralAgent. In this advanced iteration, the Central Agent evolves from a simple relay into an Intelligent Dispatcher. It continuously ingests a stream of INFORM ACL messages from the distributed LocalAgents.

Unlike amateur implementations that might trigger a kill immediately upon seeing CPU: 90%, our system exercises strategic restraint. A threshold breach acts merely as a “Probable Cause” trigger.

Technical Implementation: The dispatcher evaluates incoming telemetry against distinct thresholds for CPU and Network. Crucially, it captures the type of anomaly to inform the Scout’s mission profile.

// CentralAgent.java - The Dispatch Logic

// We distinguish between CPU and NET triggers to optimize the Scout's search

if (cpuUsage > CPU_THRESHOLD || netUsage > NET_THRESHOLD) {

String triggerType = (cpuUsage > CPU_THRESHOLD) ? "HIGH_CPU" : "HIGH_NET";

System.out.println("ANOMALY DETECTED on " + senderAgentName + ". Initiating forensic protocol...");

// Instead of executing a blind sanction, we deploy a forensic auditor.

// This prevents false positives (e.g., a system update) from being terminated.

deployScout(senderAgentName, cpuUsage, netUsage, triggerType);

}Phase 2: scout agent deployment

Upon activation, the ScoutAgent is instantiated dynamically on the server. Utilizing JADE’s Weak Mobility capabilities, it serializes its code and execution state and migrates physically to the target container (the suspicious node).

Why Mobility is Superior to RPC: Standard Remote Procedure Calls (RPC) or SSH commands would require opening distinct connections and authenticating for every command. The Mobile Agent moves once, executes locally at memory speed, and returns. This reduces network chatter and latency during high-stress scenarios.

The “In-Kernel” Inspection: Once arrived, the Scout executes a custom shell sequence designed to bypass standard user-space obfuscation. We utilize the ps command with specific flags to sort processes by the resource that triggered the alert.

// ScoutAgent.java - gatherProcesses()

// We dynamically construct the command based on the trigger (CPU vs RAM/Net)

String sortFlag = triggerType.equals("HIGH_NET") ? "--sort=-pmem" : "--sort=-pcpu";

String cmd = "ps -e -o pid,pcpu,pmem,comm " + sortFlag + " | head -6";

// Execution occurs largely in the OS kernel space for speed

Process p = Runtime.getRuntime().exec(new String[] { "sh", "-c", cmd });

// The agent parses the raw stream output into a structured report

// Format: PID;CPU%;MEM%;COMMAND_NAME

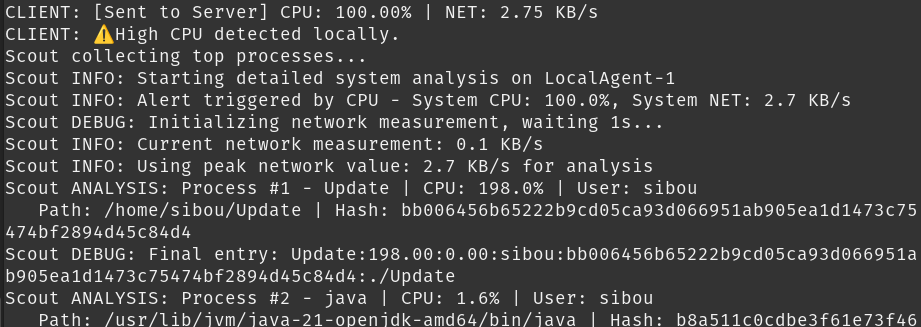

Figure 6.1: example scout report capture.

Phase 3: whitelist analysis

The Scout transmits its findings back to the Central Agent via an INFORM message with the ontology scout-report. This is where the system’s “Brain” resides.

To ensure O(1) decision speeds (constant time complexity), we implement the decision logic using a Java HashSet containing the Whitelist. This approach is faster than database lookups for this specific real-time decision.

The Logic of “Default Deny”: Security best practices dictate a “Default Deny” posture. We defined a strict set of “Immutable System Processes” (e.g., systemd, bash, java, sshd). Any process consuming >80% CPU that is not on this list is unequivocally treated as a threat.

// CentralAgent.java - The Decision Engine

private static final Set<String> WHITELIST = new HashSet<>(Arrays.asList(

"systemd", "bash", "rsyslogd", "kthreadd", "java", "sshd", "gnome-shell"

));

private void handleScoutReport(ACLMessage msg) {

// Parse the serialized report from the Scout

String[] parts = content.split(";");

String procName = parts[3]; // The command name (e.g., "stress" or "xmrig")

// The Critical Decision Point

if (!WHITELIST.contains(procName)) {

System.out.println("Alert: Unauthorized high-load process confirmed: " + procName);

// The process is high-load AND unverified.

// Authorization granted for termination.

deployKiller(containerName, procName, cpu, net, "Not Whitelisted");

} else {

System.out.println("Info: High load verified as legitimate system process: " + procName);

}

}Phase 4: killer agent response

Once a target is positively identified as hostile, the CentralAgent deploys the Killer Agent. This agent acts as a guided missile. It is initialized with a specific “Warrant” (the process name or PID) and migrates to the infected node.

Precision Termination: The Killer Agent uses pkill -f (full pattern match). This is robust against malware that might change PIDs rapidly but retains its process name.

The Feedback Loop: Crucially, the operation does not end at execution. The agent verifies the process table to ensure the threat is gone and sends a Confirmation Report back to the Central Database. This closes the control loop, providing the administrator with cryptographic certainty of the mitigation.

// KillerAgent.java - The Sanction

System.out.println("KILLER: Engaging target '" + originalProc + "'...");

// Execute termination

Runtime.getRuntime().exec(new String[] { "sh", "-c", "pkill -f " + originalProc });

// Verification and Reporting

ACLMessage report = new ACLMessage(ACLMessage.INFORM);

report.setOntology("kill-report");

report.setContent(targetContainer + ";" + originalProc + ";SUCCESS");

send(report);

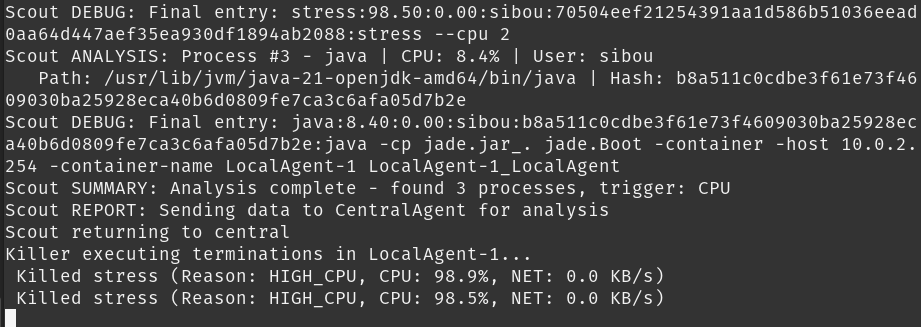

Figure 6.2: killer action confirmation.

6.3. Database logic abstraction

A critical, often overlooked design decision in this project was the abstraction of correlation logic to the Data Layer.

The Problem with Monolithic Agents:

In many academic multi-agent implementations, the Central Agent attempts to hold the entire state of the network in memory (e.g., using massive Java HashMap structures to track every node’s history). This is a fatal design flaw for scalability. As the network grows, the JVM Heap fills up, and the agent slows down, missing critical real-time alerts.

Our Enterprise-Grade Solution:

We deliberately designed the CentralAgent.java to be a stateless, high-throughput message broker.

- Statelessness: The agent handles the now. It receives a message, makes an immediate decision based on the Whitelist, and discards the state.

- Persistence Layer: All historical data is streamed immediately to the SQLite Database (network_monitor.db).

- Analytical Abstraction: The logic for detecting complex, time-based attacks (e.g., “Is this a distributed DDoS attack pattern across 5 nodes?”) is offloaded to the Web Application (Python/Flask) and SQL Queries.

Why this is superior:

- Scalability: We can monitor 1,000 nodes without increasing the RAM usage of the Central Agent.

- Query Power: SQL is optimized for correlation. A query like “SELECT * FROM metrics WHERE cpu > 90 AND timestamp > NOW() - 60s” is trivial for a database but complex to implement efficiently in Java code.

- Decoupled Visualization: The Dashboard can run heavy analytical queries (generating heatmaps, calculating averages) without blocking the JADE detection thread. This ensures that the security system never “blinks” even when the admin is generating heavy reports.

6.4. Advantages of the scout–killer approach

This architecture offers significant advantages over traditional centralized monitoring tools (like Nagios or Zabbix) in this specific context:

- Bandwidth Efficiency:

- Continuous streaming of process lists consumes massive bandwidth. By using a Trigger-Based Scout, we transmit zero process data during normal operations. We only send the ~1KB Scout Report when an anomaly actually occurs.

- Edge Computing Capability:

- The logic executes on the edge (the client node). If the network link to the server is congested, the Mobile Agent can theoretically be programmed to make local decisions, ensuring autonomy.

- Obfuscation Resistance:

- Malware often hides from network scans. By being on the box (inside the OS via the Mobile Agent), we can see exactly what the kernel sees, making it much harder for rootkits to hide their resource consumption.

6.5. Limitations and future directions

6.5.1. VirusTotal API integration

A significant limitation of the current Scout Agent is its reliance on process names for identification. A sophisticated attacker could easily bypass this by renaming malware to mimic legitimate system processes like systemd. To counter this, the system can be upgraded to calculate the SHA-256 Checksum of any suspicious binary executable. By submitting this cryptographic hash to the VirusTotal API, the Central Agent can perform a definitive lookup against a global database of known threats. This mechanism ensures 100% positive identification, exposing malware like WannaCry.Ransomware even if it disguises itself as notepad.exe.

6.5.2. behavioral anomaly detection (ML)

The reliance on a static CPU threshold (e.g., 80%) is brittle and prone to false positives. To make the system adaptive, we propose implementing a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) Neural Network or a Random Forest model. By training this AI on the network’s “heartbeat” over a baseline period (e.g., two weeks), the system can learn contextual normality. It would understand that high CPU usage at 3:00 AM on Sundays is a scheduled backup, whereas the same load at 10:00 AM on a Tuesday represents an anomaly. This shift from static rules to dynamic learning drastically reduces false alarms and eliminates the need for manual rule tuning.

6.5.3. high availability

The current architecture’s reliance on a single CentralAgent introduces a Single Point of Failure; if the central node goes offline, the entire monitoring grid is blinded. To guarantee enterprise-grade resilience, we propose implementing High Availability (HA) via Agent Replication. This involves deploying a secondary “Shadow Central Agent” on a separate physical host that continuously monitors the primary agent’s heartbeat. In the event of a failure, the Shadow Agent automatically promotes itself to master and assumes control of the database connection, ensuring 99.99% system uptime and robustness against hardware outages.

6.5.4. flow-based inspection

Current detection logic focuses solely on data volume (KB/s), leaving it unable to distinguish between a legitimate large file transfer and malicious data exfiltration. To address this, the system should integrate Flow-Based Inspection technologies like NetFlow or sFlow. By capturing packet headers rather than just volume metrics, the Local Agent can identify the geographical destination of high-bandwidth traffic. Cross-referencing this data with Geo-IP Blacklists or known Command & Control (C2) servers allows the system to block traffic destined for hostile actors or unverified external servers, effectively preventing “Low and Slow” exfiltration attacks.