shock-and-silence

The second stage of the compromise shifted from stealth to destruction. After initial access, the attacker dropped and executed ransomware, leaving behind encrypted files and a trail of renamed binaries. Using the .ad1 image, I dug through the MFT and journal logs to trace the ransomware’s origin, behavior, and identity — and it didn’t take long to uncover the full picture.

What was the original file name of the ransomware executable downloaded to the host?

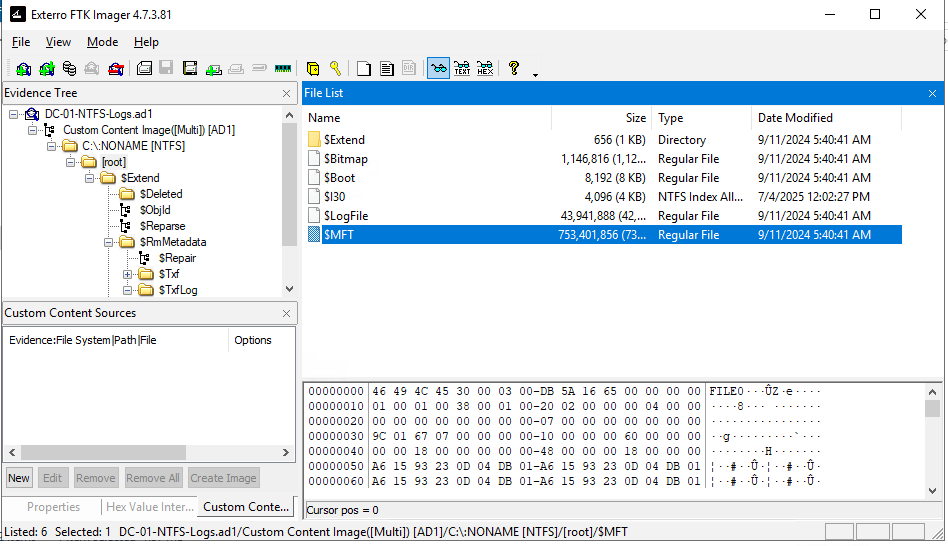

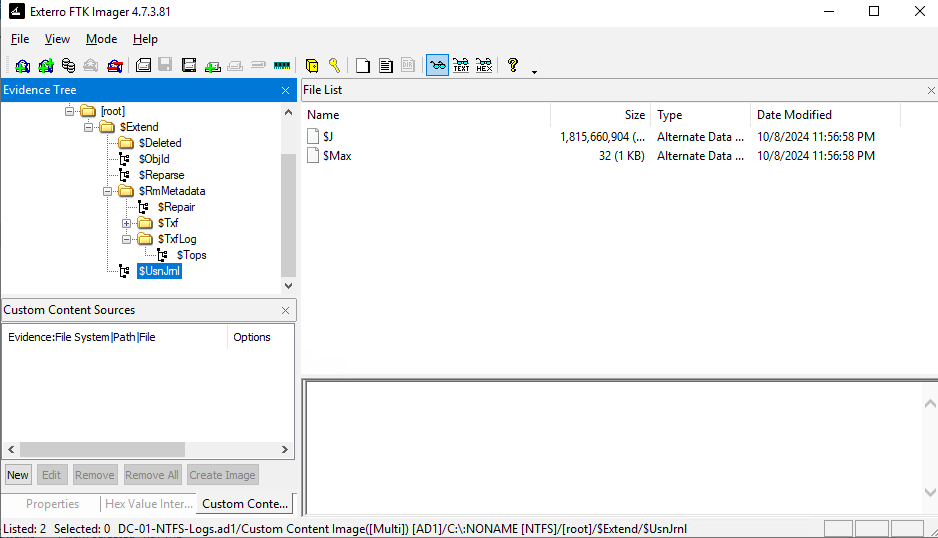

For this part, we were provided with an .ad1 forensic image. Using FTK Imager, I extracted key artifacts — specifically $MFT and $J (the journal file). These two track file creation and changes on the NTFS file system, even if files have been deleted.

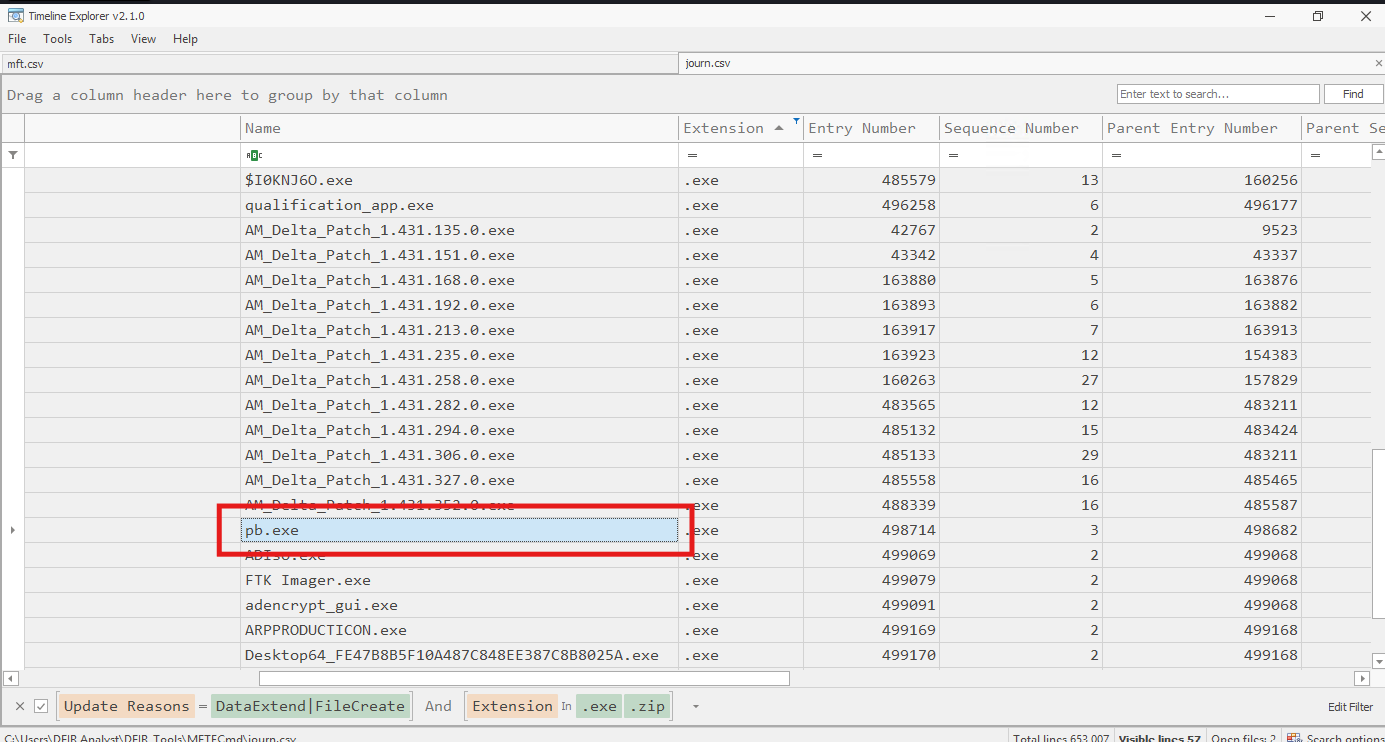

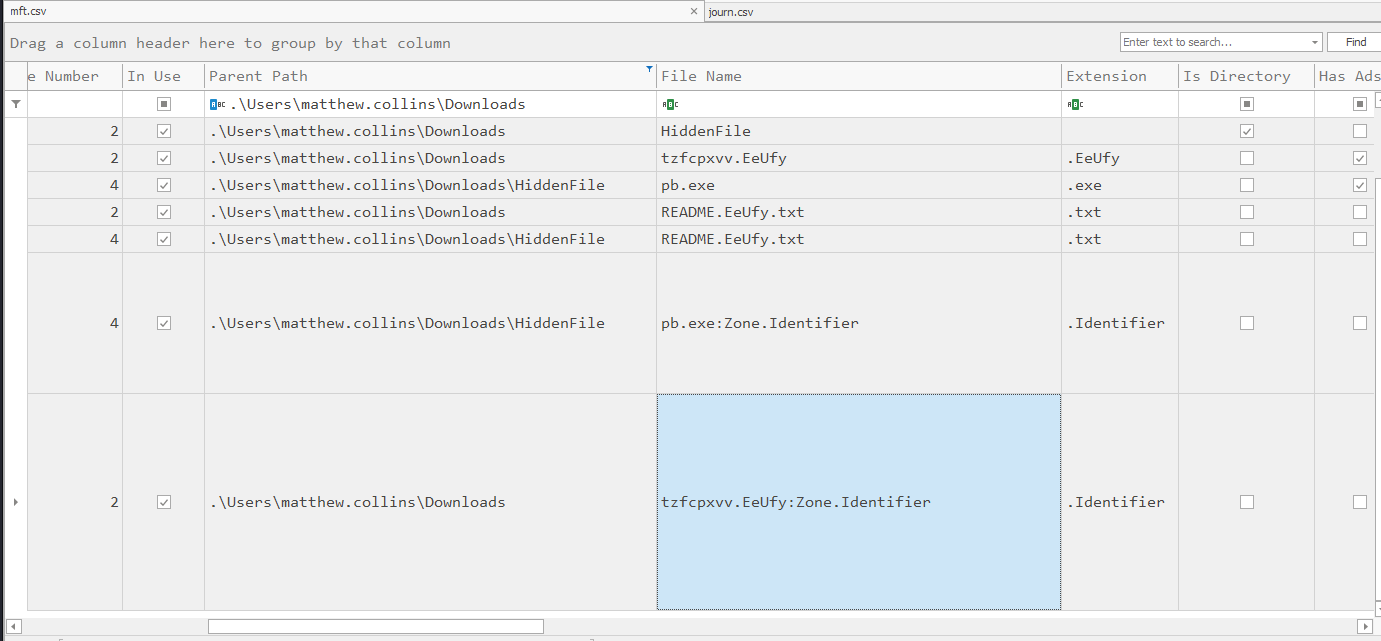

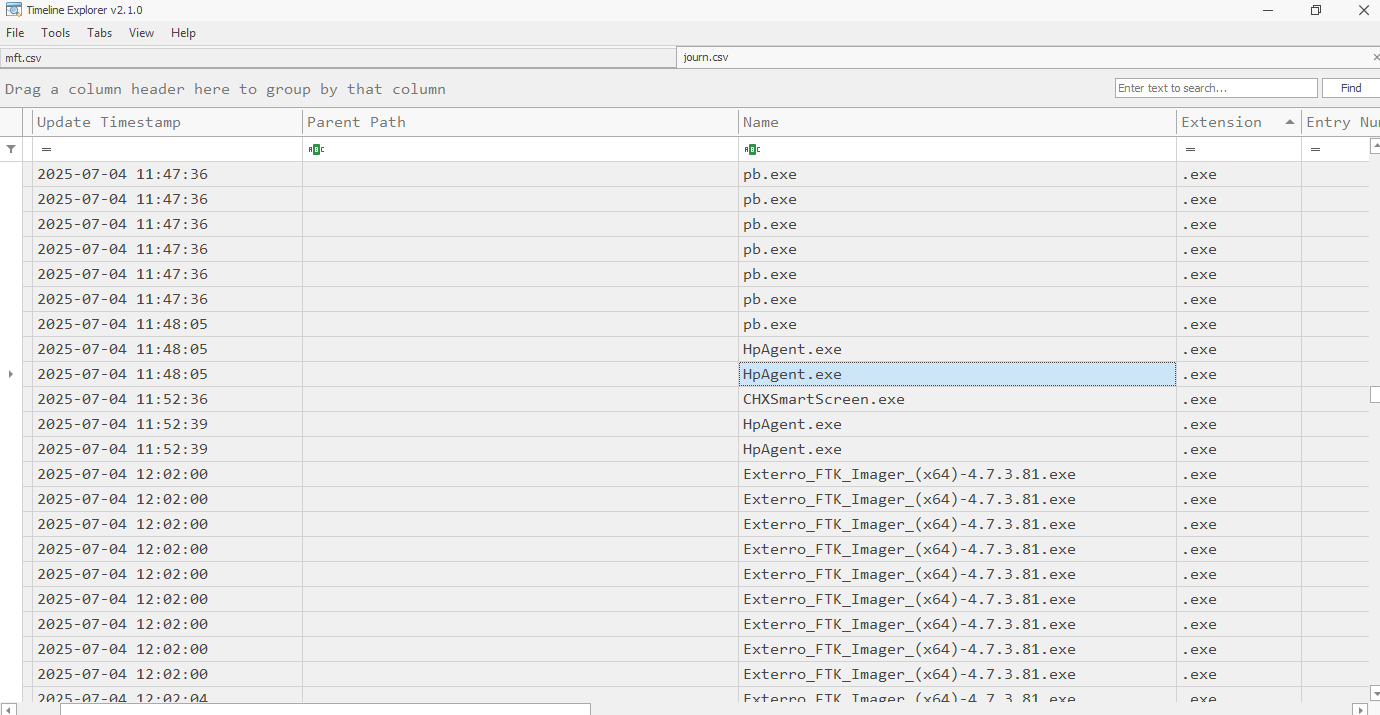

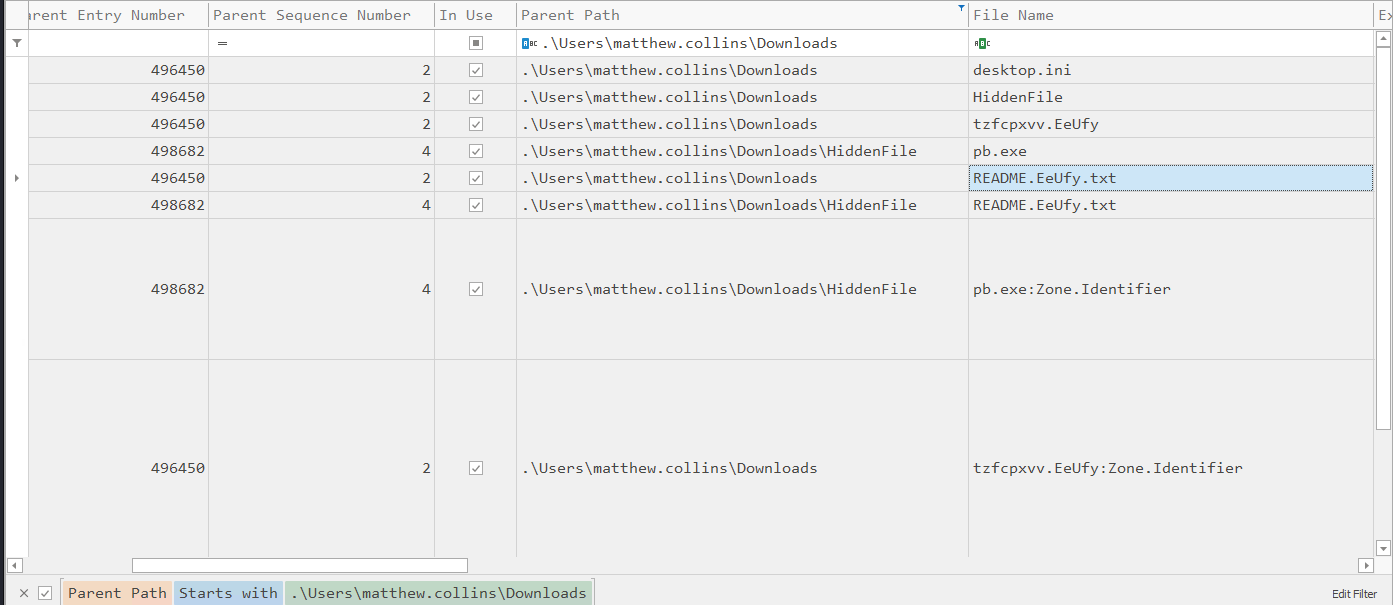

I loaded both files into MFTExplorer and exported them as .csv, then analyzed them using TimeExplorer. By filtering for .exe entries in the journal, one executable stood out: pb.exe. It wasn’t signed, wasn’t a system binary, and was only briefly present. That short lifespan is typical for malware droppers.

Answer: pb.exe

What is the full URL from which the ransomware was downloaded to the system?

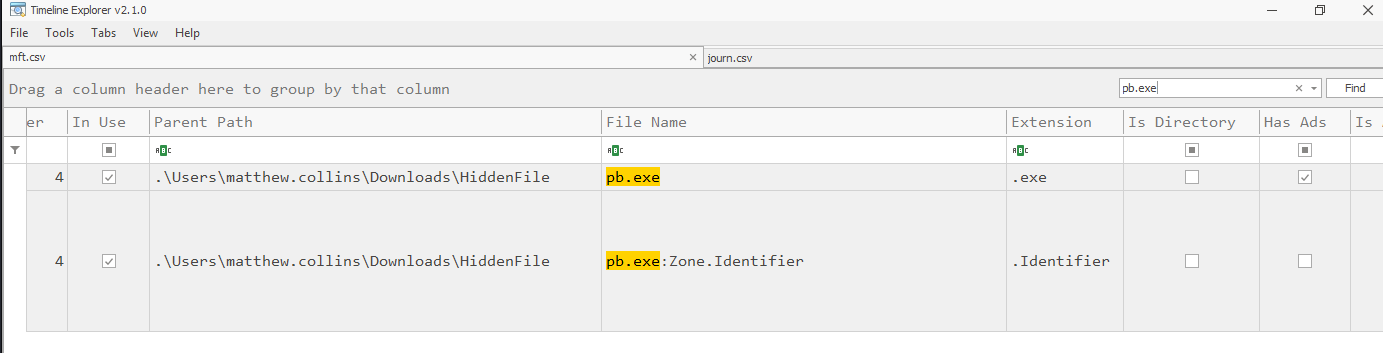

Using the MFT, I located pb.exe inside:

C:\Users\matthew.collins\Downloads\HiddenFile\\

A Zone.Identifier file (used by Windows to track files downloaded from the internet) existed alongside it.

The referrer path confirmed the local download origin:

[ZoneTransfer]

ZoneId=3

ReferrerUrl=C:\Users\matthew.collins\Downloads\HiddenFileTracing this back further, I filtered .zip entries in the MFT. One of them, HiddenFile.zip, contained the original executable. It also had a Zone.Identifier revealing the full download URL:

[ZoneTransfer]

ZoneId=3

ReferrerUrl=https://gofile.io/

HostUrl=https://store5.gofile.io/download/web/e23cb33f-0e4d-4a5f-8c55-ea2d78057d40/HiddenFile.zip

Answer: https://store5.gofile.io/download/web/e23cb33f-0e4d-4a5f-8c55-ea2d78057d40/HiddenFile.zip

Which executable file initiated the encryption process on the system?

After identifying pb.exe, I reviewed subsequent file operations in $J. Shortly after its execution, a new binary named HpAgent.exe appears. File system events indicate that pb.exe was renamed to HpAgent.exe, which is a typical evasion method to blend in with legitimate-looking binaries.

This renamed file then initiated the encryption routines seen shortly after.

Answer: HpAgent.exe

What file extension was appended to the encrypted files?

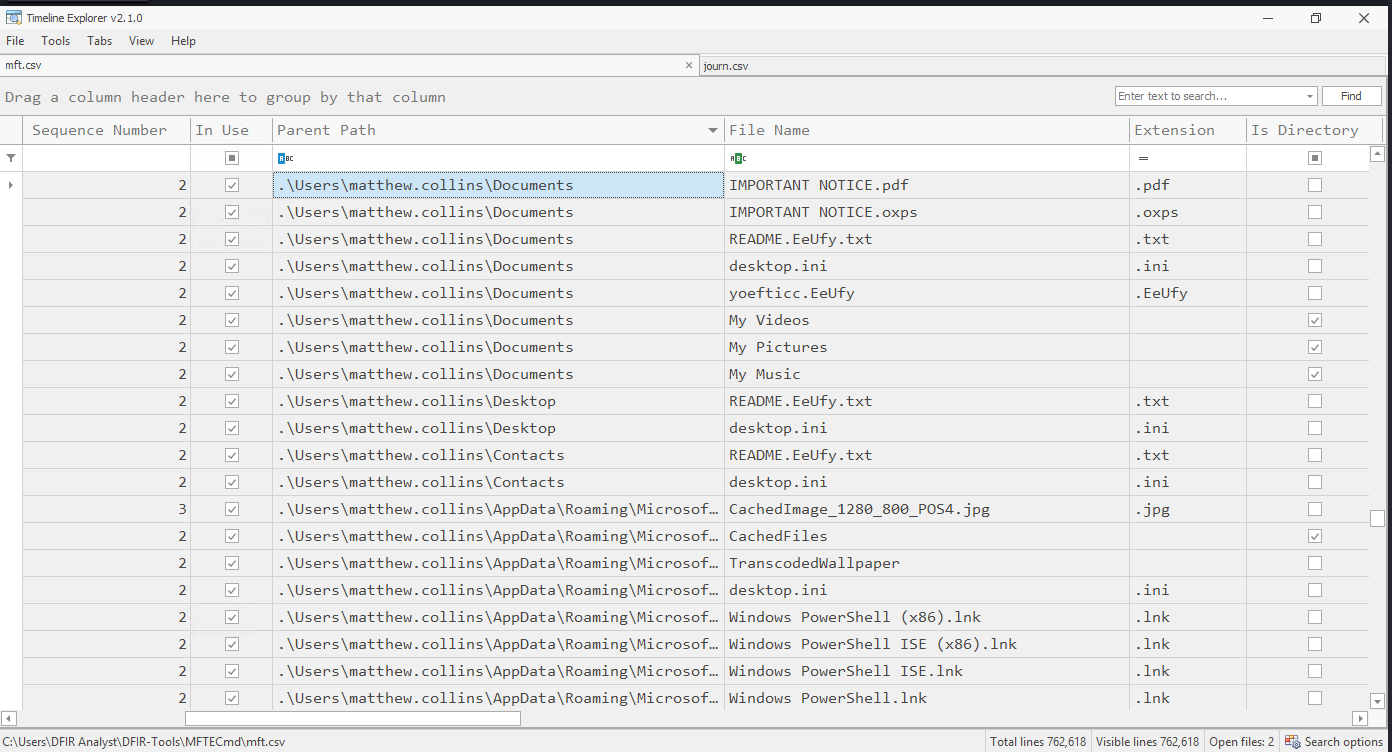

This was straightforward. A quick scan through the $MFT revealed many files with a .EeUfy extension, including ransom notes like README.EeUfy. Since this extension isn’t tied to any known app or system function, and it appeared post-encryption, it clearly belongs to the ransomware.

Answer: EeUfy

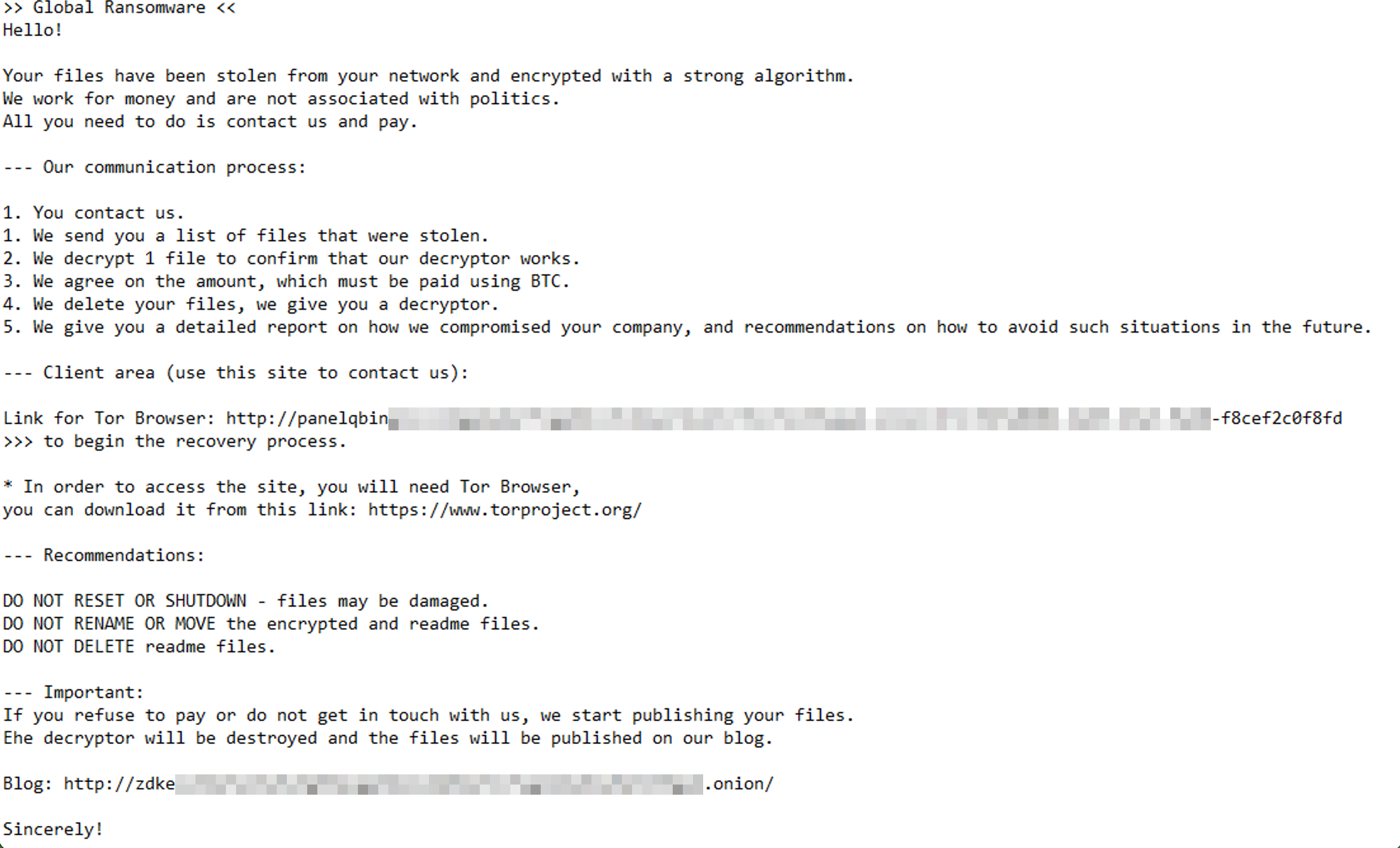

Go beyond the obvious – which ransomware group targeted the organisation?

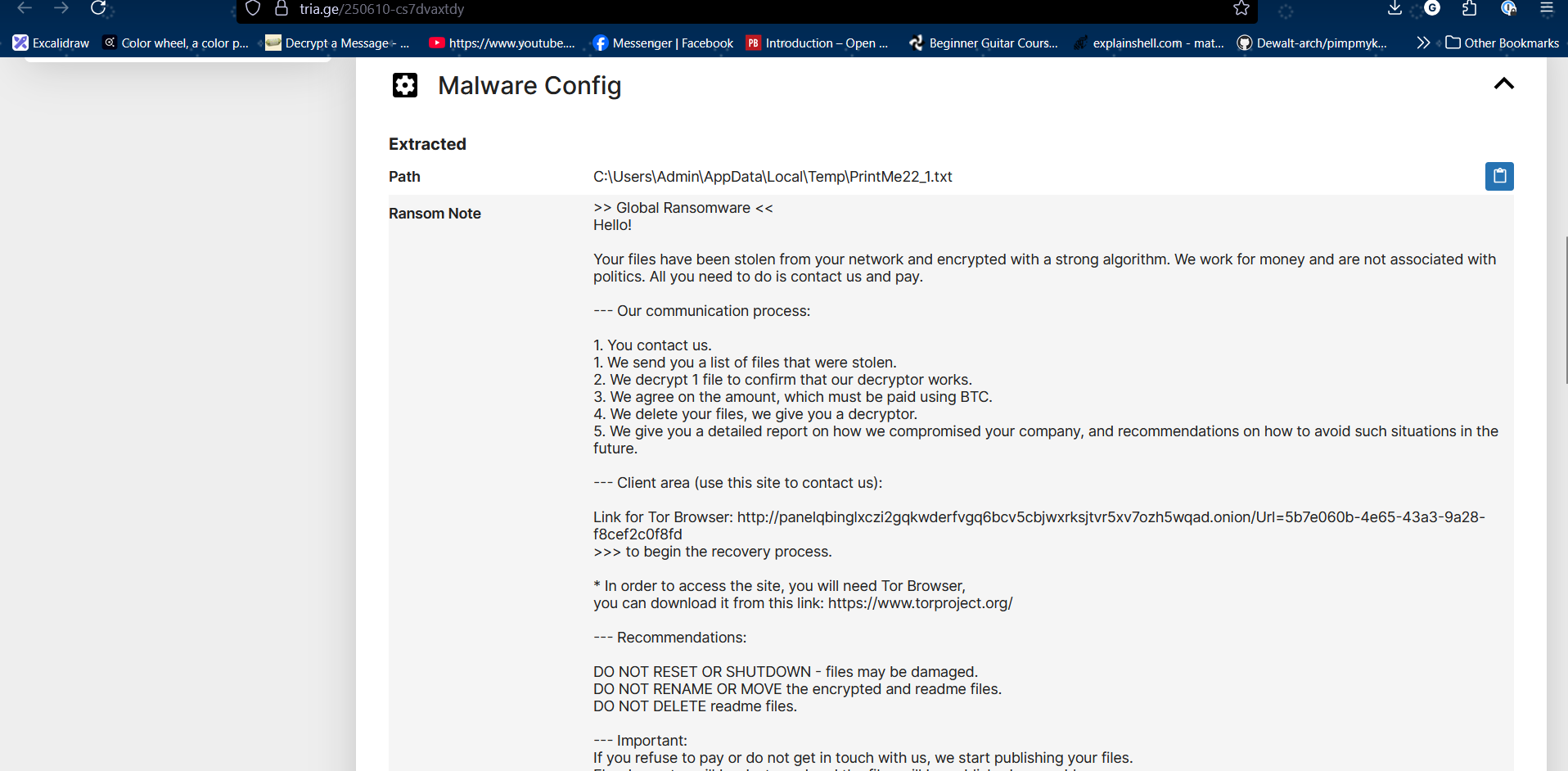

This part wasn’t purely forensic. The ransom note itself was the key. The text in the note matched a known sample indexed on tria.ge, a malware sandbox site.

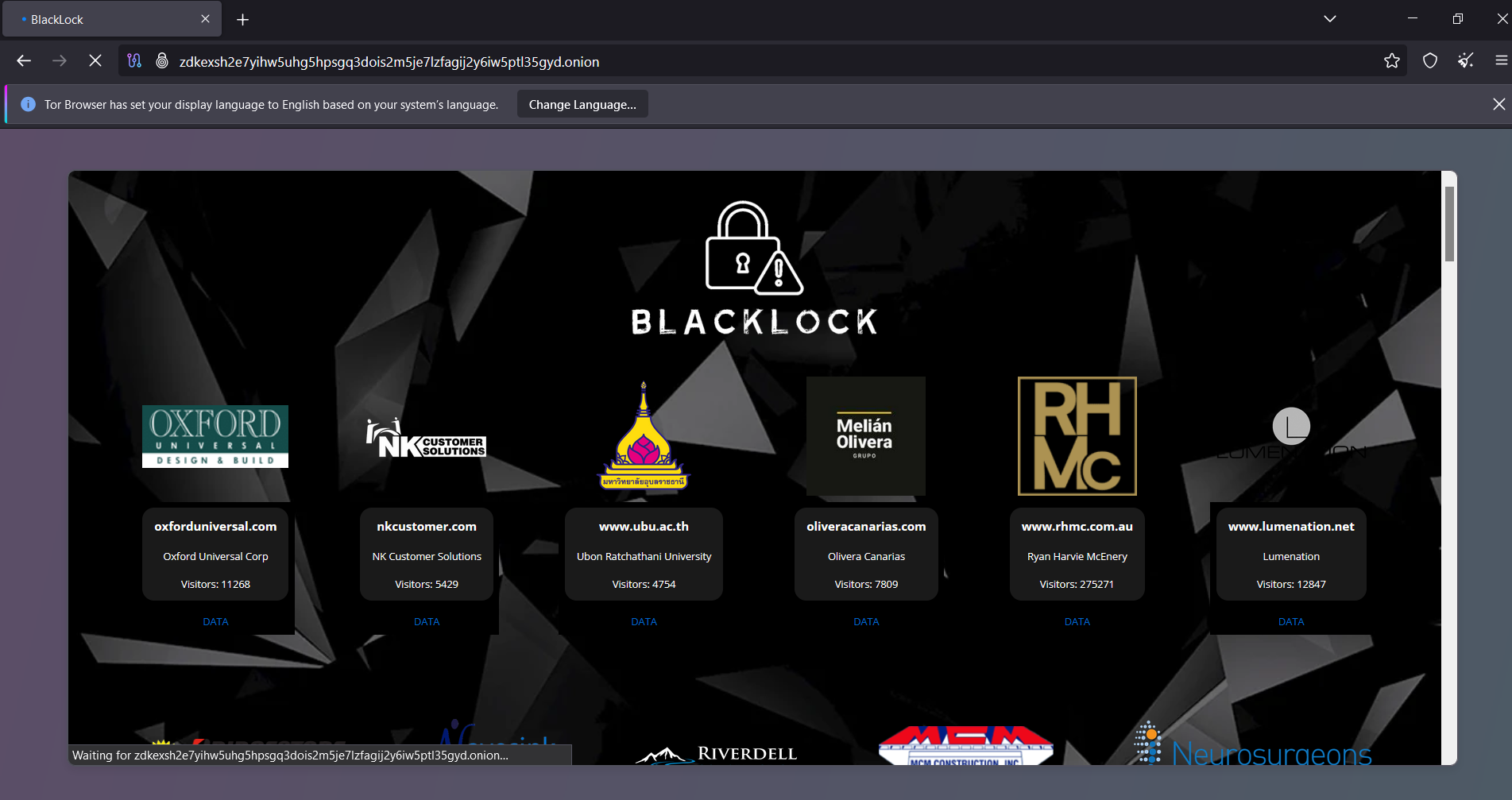

Following the link (https://tria.ge/250610-cs7dvaxtdy), I found an onion site:

http://zdkexsh2e7yihw5uhg5hpsgq3dois2m5je7lzfagij2y6iw5ptl35gyd.onion/.

Browsing it via Tor confirmed the ransomware group behind the note — BlackLock.

Answer: BlackLock

What is the filename containing additional ransom instructions for the victim?

Lastly, I searched through matthew.collins’ directories for unusual text files. Multiple copies of a file named IMPORTANT NOTICE showed up, with different extensions. Given the task hint — “filename without extension” — and the fact that the file clearly contained follow-up instructions from the attacker, this was our answer.

Answer: IMPORTANT NOTICE