elevating-movement

This section focuses on the attacker’s actions post-compromise — from the moment they logged in via RDP, to how they maintained access, escalated privileges, and eventually moved laterally across the network. By correlating event logs, PowerShell transcripts, and file timestamps, we were able to reconstruct their exact steps and expose how the breach unfolded.

When did the attacker perform RDP login on the server?

At first, I was stuck trying to find the exact login time in the Security event logs. I kept trying different timestamps, thinking I must be missing something obvious. Then it hit me — there was a “log clear” event right at the beginning of the logs. That’s usually a red flag. If the logs were cleared, it likely means the attacker tried to cover their tracks.

That led me to check an alternative source: the TerminalServices-RemoteConnectionManager log. Unlike Security logs, this one often stays untouched because it’s less obvious. I used a quick PowerShell script to extract every RDP login attempt, pulling the timestamp, user, and source IP. It was straightforward, and incredibly useful in this context.

Get-WinEvent -LogName "Microsoft-Windows-TerminalServices-RemoteConnectionManager/Operational" |

Where-Object { $_.Id -eq 1149 } |

ForEach-Object {

$time = $_.TimeCreated

$msg = $_.Message

# Extract IP address

if ($msg -match "Source Network Address:\s+([^\r\n]+)") {

$ip = $matches[1]

}

elseif ($msg -match "IpAddress:\s+([^\r\n]+)") {

$ip = $matches[1]

}

else {

$ip = "N/A"

}

# Extract User

if ($msg -match "User:\s+([^\r\n]+)") {

$user = $matches[1]

}

else {

$user = "N/A"

}

[PSCustomObject]@{

TimeCreated = $time

SourceNetworkAddress = $ip

User = $user

}

}

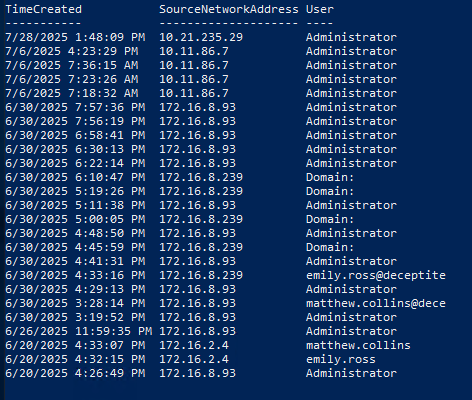

From earlier tasks and the challenge description, we already knew the attacker gained control of the emily machine and used it to pivot across the network. The log clear happened on 2025-06-30, and among the remaining entries, there’s a login from emily.ross@deceptite. That lines up with the attack timeline and confirms the attacker used her account.

Answer: 2025-06-30 16:33:18

What is the full path to the binary that was replaced for persistence and privesc?

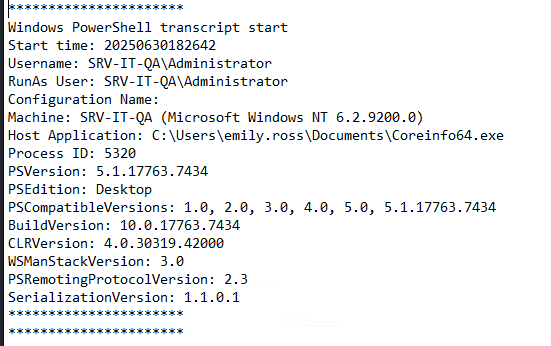

While digging through emily.ross’s user folder, I stumbled across a directory with a PowerShell transcript file. This was a goldmine — transcripts capture command history and are often overlooked.

Inside it, I noticed commands were being run under a process named Coreinfo64.exe. That caught my attention. It’s a legitimate Sysinternals tool, but here it was clearly being abused. Right after that, the transcript shows obfuscated Base64-encoded commands — another red flag.

The attacker was using a renamed or trojanized copy of Coreinfo to maintain persistence and execute malicious code, making it look like a benign tool. This is a common technique — blend in by replacing or repurposing legitimate binaries.

Answer: :C:\Users\emily.ross\Documents\Coreinfo64.exe

What type of malware payload is the replaced binary file?

Once I extracted and decoded the payload embedded in the malicious binary, everything clicked into place. The script isn’t just some PowerShell recon — it’s a full-featured Meterpreter agent, written in PowerShell, designed for stealthy command-and-control over HTTP(S) and TCP.

The malware defines functions like Add-WebTransport and Add-TcpTransport, which establish a transport layer between the victim machine and a remote attacker-controlled listener. This means once the script runs, it can reach out to the attacker’s server over web protocols (like HTTPS) or raw TCP sockets, creating a persistent backchannel for remote control.

These transports use custom settings like retry logic, proxy authentication, and even TLS certificate pinning via a SHA1 hash to blend in with legitimate network traffic or avoid interception by network security tools. In other words, it’s built to survive and keep talking back to the attacker no matter what.

But it doesn’t stop at transport setup.

The script also loads modules from the MSF.Powershell.Meterpreter.Kiwi namespace — a clear reference to Mimikatz functionality integrated into Meterpreter. There are three major functions here that make it dangerous:

- Invoke-DcSync: Allows the attacker to request password hashes from a domain controller remotely, using the same method domain controllers use to sync user credentials with each other. This function doesn’t need the attacker to be on the DC — it just needs the right privileges.

- Invoke-DcSyncAll: Scales this up to extract all user hashes from the domain. Even accounts that are usually ignored, like disabled ones or machine accounts (the ones ending in $), can be optionally included.

- Invoke-DcSyncHashDump: Automates the process of pulling and dumping all user hashes from the target domain controller into a format that can be used offline — for cracking, replay attacks, or pivoting further across the network.

The script even calls [MSF.Powershell.Meterpreter.Core]::SetInvocationPointer() — a lower-level call that modifies runtime behavior of the Meterpreter session, possibly for evasion or control-flow manipulation.

This is not a simple reverse shell or one-liner payload. It’s an advanced post-exploitation toolkit embedded in PowerShell. It provides the attacker with:

- Multiple persistent transport options

- Credential theft through DCSync and LSASS dumping

- Proxy and certificate support to evade detection

- Full integration with Metasploit’s automation and payload delivery systems

There’s no doubt this is a custom-built PowerShell Meterpreter payload — a hallmark of the Metasploit Framework — and it’s been enhanced with Kiwi (Mimikatz) modules for lateral movement and full domain compromise.

Answer: Meterpreter

Which full command line was used to dump the OS credentials?

Toward the end of the PowerShell transcript, right after the main malicious payload had run, there’s a very telling command:

pcd.exe /accepteula -ma lsass.exe text.txtThis command dumps the memory of the lsass.exe process — the Local Security Authority Subsystem Service. LSASS is responsible for handling credentials, so attackers often target it to extract hashes or plaintext passwords.

The /accepteula flag is a typical way to suppress GUI prompts in Sysinternals tools. And dumping LSASS is a classic move to harvest NTLM hashes.

Answer: pcd.exe /accepteula -ma lsass.exe text.txt

Using the stolen credentials, when did the attacker perform lateral movement?

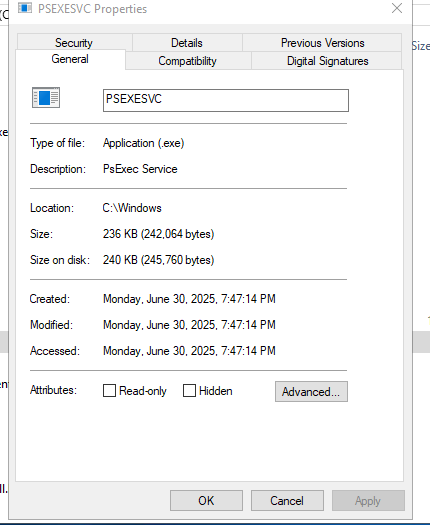

This one took a while to crack. It wasn’t logged clearly anywhere I expected. No obvious entries in standard logs, no alerts — nothing. Eventually, I found something buried in the file properties of a very specific executable: PSEXESVC.exe.

That file is part of PsExec, a tool that allows execution of commands on remote systems. It’s used by admins — and attackers — for remote control. What caught my attention was its last accessed timestamp. Since PsExec only runs when called, that timestamp is a strong indicator of when the lateral movement occurred.

Given the context and the timeline, that timestamp lines up exactly with the moment the attacker pivoted to another machine using stolen credentials.

Answer: 2025-06-30 19:47:14

What is the NTLM hash of matthew.collins’ domain password?

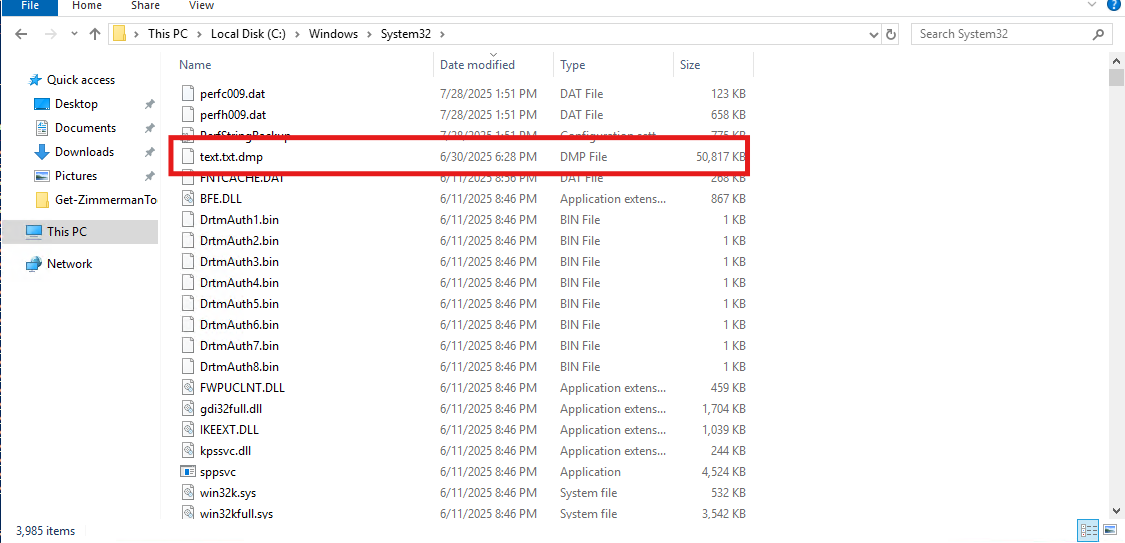

We already know the attacker dumped LSASS to text.txt.dmp. What wasn’t immediately clear was where they stored it. While scanning through System32, I noticed one file had a very recent timestamp that stood out — too new to be normal system activity.

It turned out to be the dumped file. Clever move by the attacker — hiding something in plain sight, in a system directory where people might not think to look for artifacts of compromise.

I copied the file over using RDP and ran it through pypykatz, a tool for parsing LSASS dumps. It extracted several credentials, and among them was the NTLM hash for matthew.collins.

Answer: eb3d2de2f21b31933fb4a4fd7a7d314d